One of the interesting findings coming out of the Toowoomba recycled water controversy was that residents were put off because the council couldn’t offer a 100% guarantee that the water was safe. This raises interesting issues around the perception and communication of risk.

From a scientist’s perspective, risk is a combination of the likelihood an event will occur and the consequences of the event occurring.

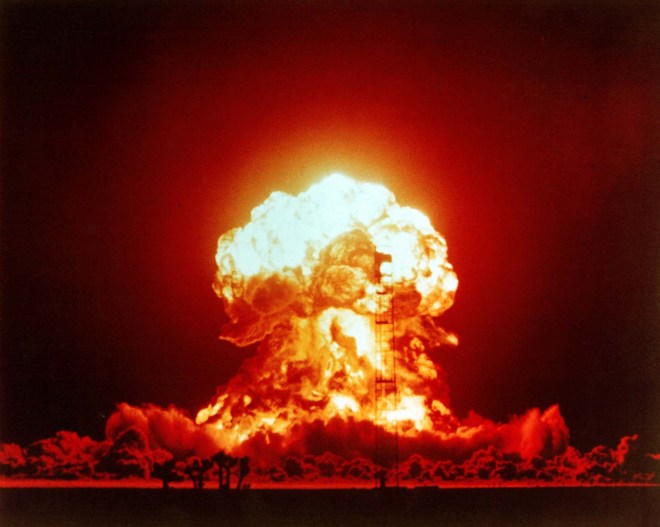

For example, the likelihood of a nuclear reactor melting down are tiny but the consequences are catastrophic. Whilst the chances of a severe thunderstorm occurring on a given day in Sydney are much higher, the consequences are much less severe.

A nuclear accident may have a low likelihood but devastating consequences. Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration / Nevada Field Office.

Research shows the general public views risk quite differently to scientists*. Us non-specialists carry a much broader notion of risk that incorporates accountability, economics, values and trust.

In Toowomba, the delay by council in their initial communication about the recycled water plant lead to a loss of public trust. This was likely because the risk vacuum created was filled by an anti-recycled water activist group. It may also be that while focusing on the risk statistics, there was a lack of acknowledgment about other values that the public felt were threatened by the scheme – the image of the town as Poowoomba.

Studies of risk communication show that communication of zero risk is doomed to failure. While this was not the issue in the Toowoomba case, early loss of trust in decision-makers made subsequent communication difficult. With earlier and better engagement, discussion about values may have taken place. There may even have been a chance to put the case for economic opportunities associated with having more water, and how a more stable water supply could benefit key values of the town such as their gardens.

* Leiss, W. (2004). Mad cows and mother’s milk: the perils of poor risk communication. McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.